Birmingham, Ala., witnessed so many bombings during the Civil Rights Movement that it became known as “Bombingham.”

The most famous of those bombings was at the 16th Street Baptist Church on Sept. 15, 1963, in which Addie Mae Collins, 14; Cynthia Wesley, 14; Carole Robertson, 14; and Carol Denise McNair, 11; were killed when a box of dynamite was placed under the church’s stairs by members of the Ku Klux Klan.

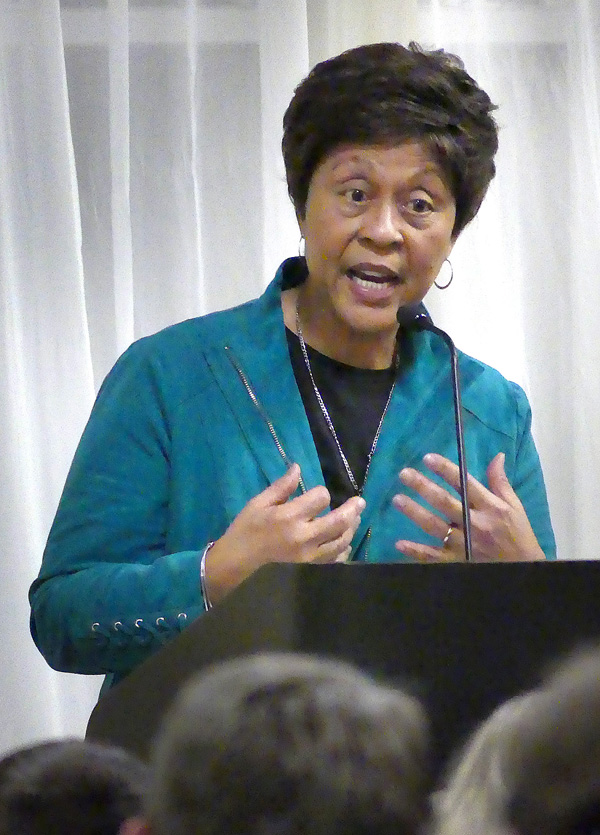

A survivor of that tragedy – Dr. Carolyn Maull McKinstry – spoke to a packed room at Westminster Hall, Grace College, in Winona Lake, Monday evening, bringing with her a message of love, forgiveness and reconciliation.

“I have traveled, to date, to nine countries and 42 states … in the name of love and forgiveness and reconciliation. And I greet you with that love today in the same spirit of love and reconciliation,” McKinstry said.

She stated that 1963 was a “pivotal” year in the life of this country. It was the year that George Wallace – a symbol of segregation – became governor of Alabama and stood in the doorway of the University of Alabama to keep black students from enrolling; Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested and locked up in the Birmingham jail; there were the Children’s Marches, of which McKinstry participated in, broken up by police attack dogs and water hoses; King led a march on Washington with more than 250,000 people; and John F. Kennedy Jr. was assassinated.

On Sept. 30, 1963, police arrested Robert Chambliss, Charles Cagle and John Hall in conjunction with the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, but they were all released and given a $100 fine. Many years later, McKinstry would be subpoenaed to testify about the bombing against the men. “This was a critical year for someone who was 14 years old,” McKinstry said of 1963. She read some of the Jim Crow laws that existed then. One sample was that “colored persons may not address white persons by their given names. They must always use titles of respect, i.e. Mr., Mrs., Miss, Sir or Ma’am. Whites must not use courtesy titles of respect when referring to blacks.”

“If you happened to have been living in Birmingham in 1963, around that time Martin Luther King had come to town, you would have heard King describe Birmingham as a city of hardcore resistance. The most segregated city in the south,” McKinstry said. “If you had been there with Birmingham’s first African-American mayor, Dr. Richard Arrington Jr., you would have heard him say that Birmingham was a city that needed to be born again. If you were listening to international media, you would have heard them referring to Birmingham as ‘America’s Johannesburg.’”

When McKinstry was a young girl in school, she said she received three introductions to segregation. The first was when her grandmother was brought to Birmingham for medical treatment but was put in a hospital’s basement. The second was when she won the state spelling bee championship, but couldn’t go to nationals because of the Jim Crow laws. The third was the church bombing.

16th Street Baptist Church was built in 1901 by African Americans who were less than 50 years removed from slavery. The church cost $36,000 but the parishioners owed nothing when they walked into it for the first Sunday, McKinstry said. “It was a beautiful place to be,” she said. Parishioners included black doctors, store owners, teachers and more. “They created a self-contained community. If I was missing anything, I didn’t know I was missing it because no one talked about it.”

She said Birmingham citizens of color had adapted to the city life and pushed for good things for their children. “I can tell you that when I marched with all of those students, the records tell us that we were over 5,000. When I marched with them, there’s absolutely no record of anyone getting shot or killed, whether they were white or whether they were black. There just wasn’t fighting, there just wasn’t killing. We marched. We were obedient,” McKinstry recalled.

When King had the meeting at the church to help with the march, “One of the things he said was ‘the most important thing about this march is to maintain the integrity of the non-violence aspect. If you can not maintain that integrity, we ask you that you step aside,’” she said. The church had become intertwined with the Civil Rights Movement.

On the morning of Sept. 15, 1963, 14-year-old McKinstry arrived at 16th Street Baptist Church at about 9:30 a.m., with her two younger brothers. That morning was youth day, and everyone had a role to play. The lesson for the day was “A Love that Forgives” from the Book of Luke.

As secretary, she collected all the money from the downstairs and headed upstairs. When she reached the top of the stairs, the phone was ringing in the office. When she answered it, the caller on the other end said, “Three minutes.” No one had told the children about the threats to the church.

The bomb exploded at 10:22 a.m. McKinstry spent the next 20 years in depression, struggling with what happened at the church. It was the second bombing she had experienced, with the first being that previous April across from her family’s home.

“If you visited the church today, you are not able to touch the space where the girls were. We sealed that space off. We put a wall,” she said. “We sealed it because when they bombed the church, there were already over 60 unsolved bombings, but all of the 60 were black homes, black businesses and black churches. So we didn’t really think anybody was going to go to jail for that, so we sealed it off so when you came into the church, you didn’t have that memory.”

During the time she was struggling with the bombing, McKinstry said, “God gave me a message, and the message was, ‘Carolyn, you have to love. You must learn to love. You must learn to forgive.’” She understands now that forgiveness is for the person who has been wounded as “it allows you to move freely, to put that aside and move on.” McKinstry also talked about the responsibility people – especially Christians – have to God and each other to be reconciled.

After a short video, the floor was open to questions. The last question, from Warsaw student Finn Bailey, was, “How can I as a child communicate this message of love and reconcilation to students my age?”

McKinstry responded, in part, “Earlier today, someone asked me what I saw as the hope for the future. I said to them, ‘Our hope for the future is our young people.’ I’m constantly watching the things that young people are doing all over the country – Parkland, Florida; the lady whose picture appeared on Time magazine. As for you, setting the example that you want to see.”