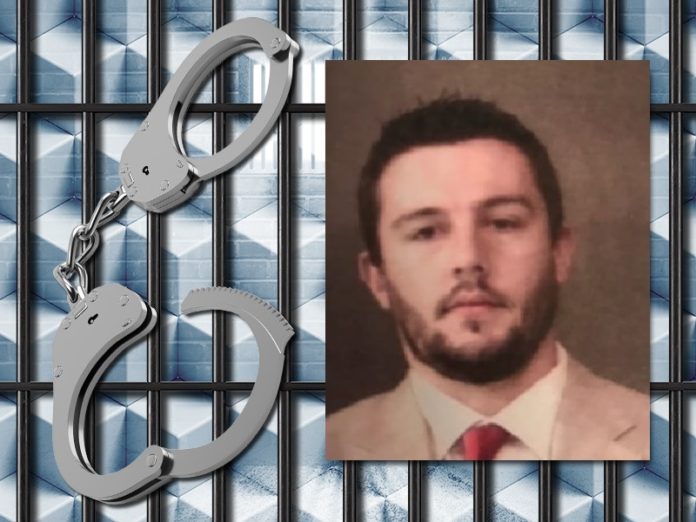

A motion to dismiss both charges against Patrick Olson has been filed by his attorney, David Kolbe, of Warsaw.

Olson, of Winona Lake, is a former Kosciusko County Community Corrections home detention officer who was charged in October 2017 with aiding an escape by removing a woman’s ankle bracelet monitoring device. He and the woman then traveled to Valparaiso and spent the weekend together.

On Jan. 10, Olson decided to take his case to a jury trial, which is scheduled for Nov. 19-22 in Kosciusko County.

The motion e-filed Monday evening in Kosciusko County Superior Court I states that Olson was denied a speedy trial; the court doesn’t have jurisdiction with respect to Count I (sexual misconduct with a service provider) as the county of proper venue is Porter; and the facts alleged in the probable cause affidavit with respect to Count II (aiding, inducing and causing escape) do not constitute an offense.

It also says Olson was denied procedural due process of law by the failure of the court to set any stated term for the special prosecutor (D.J. Sigler, of Whitley County); the failure of the special prosecutor to file any progress reports; the failure of the special prosecutor in his acceptance and oath to support the U.S. Constitution; and in the unlawful selection procedure of the special prosecutor.

Kolbe’s memorandum supporting the motion to dismiss states that the charges against Olson were filed in Superior I on Nov. 17, 2017, with the warrant served that day and Olson taken into custody and a bond posted.

Prior to the filing of the charges, Marshall County Superior Court I Judge Robert O. Bowen was appointed as special judge. Also on Nov. 17, 2017, Kosciusko County Prosecuting Attorney Daniel H. Hampton filed a motion to appoint Sigler as the special prosecutor.

Kolbe argues the case should be dismissed pursuant to Criminal Rule 4(C), which provides that “no person shall be held on recognizance or otherwise to answer a criminal charge for a period in aggregate of more than one year from the date of the criminal charge against such defendant is filed, or from the date of his arrest on such charge, whichever is later.”

He states that Indiana law is clear that unless the case is brought to trial within 365 days, all charges must be dismissed with prejudice. This period is extended where any delay is caused by the defendant’s actions.

Kolbe states the charges were filed Nov. 17, 2017, and provides a timeline of the case, listing the dates of several hearings, motions and conferences.

By Jan. 10, Kolbe says, 419 days transpired with 28 days assessed against Olson, for a total of 391 days assessed against the state.

Kolbe says a jury trial was set on Jan. 10, well outside the 365-day deadline, violating Criminal Rule 4(C) and therefore Olson is entitled to a dismissal.

The motion also argues that Count I must be dismissed because Kosciusko County is the improper venue. Venue is jurisdictional.

“Clearly, the state, in its affidavit of probable cause, unequivocally reveals that the alleged act of sexual misconduct occurred in Valparaiso, Porter County, Indiana,” the motion states.

The probable cause affidavit states Olson was the escapee’s case manager and their relationship turned into more. She said Olson came to her home, removed her ankle bracelet and they went to Valparaiso, staying two nights in a hotel room together. During the weekend, they had sex.

Kolbe cites Indiana Code which says “criminal actions shall be tried in the county where the offense was committed.” Based on that, Kolbe said Count I was filed wrongfully in Kosciusko County and the count should be dismissed.

Then he argues that the facts alleged in Count II affidavit do not constitute an offense.

The state alleges in the count that Olson “aided, induced or caused Chelsea Robison to remove her electronic monitoring device.” The question then is whether Robison removed her electronic device in violation of law, but Kolbe says the probable cause affidavit revealed the answer is “no.”

The investigating officer asserts in the affidavit that “Officer Olson came to her residence and (she) advised he had removed her ankle bracelet.”

Kolbe states there is “no allegation that Chelsea Robison requested that Mr. Olson remove the device nor that she assisted or participated in any way in its removal. It was solely allegedly carried out by Mr. Olson. One can only commit aiding, inducing or causing if another person commits that offense.”

He also says, “Given all of the allegations contained in the probable cause affidavit, Chelsea Robison did not knowingly or intentionally remove an electronic monitoring device or GPS tracking device.”

Next, Kolbe argues that Olson was denied procedural due process regarding the special prosecutor. All persons charged with crimes are entitled to federal due process of law, he states, quoting Indiana Supreme Court case upholding due process.

He says the state failed to establish the length of the appointment of Sigler as special prosecutor, and “no person should be held under the scrutiny of a special prosecutor without time and accountability mandates.” Kolbe says Olson’s due process rights were violated by virtue of the court’s failure to comply with the law.

He also points out that Indiana Code mandates that the special prosecutor submit at least one time every six months a progress report, and Sigler failed to file any.

Sigler’s selection also was unlawful, Kolbe contends. Hampton filed a motion for a special prosecutor on Nov. 17, though he previously filed the charges and assigned the case to deputy prosecuting attorney J. Brad Voelz. “Only after the filings did Mr. Hampton allege that there existed an appearance of impropriety as Mr. Hampton served on the Community Corrections Board. Mr. Olson asserts that this appearance of impropriety issue existed before Mr. Hampton’s decision to file charges.” Further, Kolbe states that Hampton’s motion for a special prosecutor signaled to the court who should be appointed and that the order appointing the special prosecutor was prepared by Hampton and filed with the motion.

“This flies in the face of the necessity to remove oneself from a case and permit the special judge to make an unfettered decision as to whom to appoint as special prosecutor. What happened was a patent due process violation,” Kolbe contends.

Another point Kolbe makes is that Sigler only affirmed he would support the Indiana Constitution and failed to affirm he would uphold and comply with Olson’s federal constitutional rights.